You’ve just finished Brooke Bolander’s The Only Harmless Great Thing, and maybe you’re blinking back tears at the Many Mothers’ song of man’s undoing, “the joining, teaching, come-together song.” Maybe you’re angry at the injustices endured by humans and elephants alike. Maybe you don’t yet know how to feel and are still sitting with this powerful tale. But I bet you want more.

While this satisfying, self-contained novelette draws a clear line from a reimagining of Topsy and the Radium Girls to an alternate future reshaped by the elephant’s fate, there are so many plot threads that deserve their own detours. This list is all about exploring those branching paths: There’s further reading on Topsy’s long life and the Radium Girls’ drastically shortened ones, in exhaustively researched and compassionately presented nonfiction. Or, if The Only Harmless Great Thing has whetted your appetite for more speculative tales of sentient elephants and nuclear warnings, you’ll find new additions to your TBR stack that will make it feel like Topsy, Regan, and Kat are all still with you. And if Bolander’s language is what grabbed you, then we’ve got a lyrical, David Bowie-loving poet we’d like to introduce you to…

The Radium Girls: The Dark Story of America’s Shining Women by Kate Moore

Buy the Book

The Radium Girls

If you cried for Regan and Jodie: While Regan and Topsy meet in an alternate-history United States, the details of Regan’s job painting fluorescent watch-dials—and how the radium begins counting down the rest of her short life—are grimly accurate. In this deeply researched (but not for the faint of heart) book, Moore speaks up for the factory workers, the “shining women,” whose dream jobs helping the war effort left them with rotting jaws and shortened lifespans. From Marie Curie’s discovery of radium to the sensational trial against US Radium, the dark history of this wonder element is revealed.

Also consider checking out Lauren Beukes’ The Shining Girls, which puts its own twist on the nickname as a serial killer with a time-traveling house stalks a number of chosen women through the decades. One of his victims is Miss Klara, a savvy showgirl who draws inspiration from the Radium Girls for her act. The Glow Girl’s short and tragic life is only a chapter of the book, but it really grounds the serial killer’s time travel, placing him in and out of the paths of these poor “shining girls,” including this very literal one and her glowing trophy he snatches for his collection.

Barsk: The Elephants’ Graveyard by Lawrence M. Schoen

Buy the Book

Barsk: The Elephants' Graveyard

If you could spend hours signing with elephants: Neither the explanation for the elephants’ sentience nor the history behind the adoption of Proboscidian as sign language are explained in the novella—but admit it, it just made sense, right? Bolander isn’t the only author who considered what would happen if humans uplifted elephants into a higher plane; in Barsk, Lawrence M. Schoen explores a future where the human race is a footnote and all manner of sapient animal races subjugate, destroy, and rely on one another. The Fant are an ostracized species, exiled to the rainy planet of Barsk but also keepers of medicines that could cure the rest of the animal kingdom, spread across the stars. In this novel (and its follow-up, The Moons of Barsk), Jorl, a Fant Speaker with the dead, must interrogate the ghost of his best friend to unearth a secret—while the deceased Fant’s son Pizlo, a physically challenged child who feels no pain, takes his first unsteady steps toward the future that only he can see.

While Barsk is a ridiculously perfect fit, The Only Harmless Great Thing’s meditation on how sentient animals are used for the material benefit of humans also uncannily brings to mind Robert Repino’s Mort(e). Check out it and ten other tales of anthropomorphic animals!

Mandelbrot the Magnificent by Liz Ziemska

Buy the Book

Mandelbrot the Magnificent

If you dig historical science retellings: What if there were a magical layer lending urgency to Benoit Mandelbrot’s early mathematical explorations during World War II? Where the rest of us see fractals spinning off into infinity, Mandelbrot identifies minute pockets into parallel universes. Ziemska’s magical pseudo-biography reimagines the mathematician’s childhood during Hitler’s rise to power: in an era where people like Mandelbrot’s family were fleeing their homes to escape the growing evil, young Benoit discovers secret dimensions in which to hide, all unlocked by math. Talk of Kepler’s ellipses transports Benoit; archetypal math problems about approaching infinity provide him with glimpses into mirror worlds in which he can hunt monsters. But as the monsters in his world abandon all pretense of peace, Mandelbrot must harness his gifts to hide his family, or else he’ll have sealed their fates.

Life on Mars by Tracy K. Smith

Buy the Book

Life on Mars

If the poetic interludes about Furmother-With-the-Cracked-Tusk’s search for the Stories gave you life:

We like to think of it as parallel to what we know,

Only bigger. One man against the authorities.

Or one man against a city of zombies. One manWho is not, in fact, a man, sent to understand

The caravan of men now chasing him like red ants

Let loose down the pants of America. Man on the run.Man with a ship to catch, a payload to drop,

This message going out to all of space. . . .

These lines from U.S. Poet Laureate Tracy K. Smith’s “My God, It’s Full of Stars” have the same lyrical, sweeping quality as the poetic portions from the elephants’ perspectives. But instead of diving into the Blacksap lake, Smith carries you up into the stratosphere. Fran Wilde puts it better than I can: “She puts her hand out into space and draws starstuff down to the page.”

A Canticle for Leibowitz by Walter M. Miller, Jr.

Buy the Book

A Canticle for Leibowitz

If you had complicated feels about nuclear warnings for future generations: The part of The Only Harmless Great Thing that most grabbed me was the alternate-universe present-day plot in which Kat tries to convince the elephants to submit to genetic alteration so that they glow in an eerie approximation of radiation. Serving as living beacons warning humans away from nuclear waste sites, they would be altering the purpose of their entire race, at little benefit to themselves besides possessing the irradiated land. It’s the kind of proposal that would not be out of place for the field of nuclear semiotics, which seeks a way to communicate the dangers in a universal way that could account for changes in language, understanding, and civilization for centuries or millennia to come.

Miller’s seminal novel explores the alternative: What if, after nuclear war nearly wipes out civilization, the survivors outlaw all of the advanced knowledge that got humanity into trouble in the first place? Electrical engineer Isaac Edward Leibowitz’s “booklegging” of precious texts inspires a monastic order and later elevates him to sainthood. Over the thousands of years that this novel spans, the order’s abbey fights to preserve the “Memorabilia,” or collected writings that Leibowitz first saved from the self-named “Simpletons.” It’s no glowing elephant, but it’s an equally chilling vision of the future.

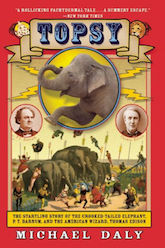

Topsy: The Startling Story of the Crooked-Tailed Elephant, P.T. Barnum, and the American Wizard, Thomas Edison by Michael Daly

Buy the Book

Topsy

If Topsy is your Patronus: Topsy’s story is never not going to be tragic, though writers like Bolander at least give her a final fuck-you to her abusers, or weird little tributes like that Bob’s Burgers episode (below) create delightful songs to remember her by. Knowing her fate, readers and writers have no other choice but to fill in the blanks leading up to that day in Coney Island as best they can. Daly’s illustrated nonfiction book, in particular, handles Topsy’s story with sensitivity and surprising compassion: He simultaneously acknowledges that while she had killed at least one man, she was also cruelly mistreated by spectators and handlers alike. As the New York Times Sunday Book Review puts it, “Daly works hard to let us know exactly what is lost each time an elephant is beaten or killed.” While still a difficult read, it at least acknowledges the intelligence and life in its subject.